A Gentle Introduction to React Hooks

JavaScript Chats with ACM Hack Session 3

October 21, 2019

- Quick Review of the

classLifecycle Methods - Quick Review of Function Component

- Overview of Hooks

- 2 Rules of Hooks

- 🍏Application: "Power of Hooks" with Debouncing

- Final Challenge

Quick Review of the class Lifecycle Methods

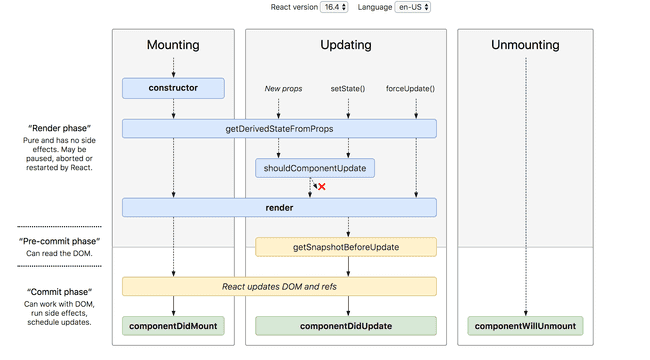

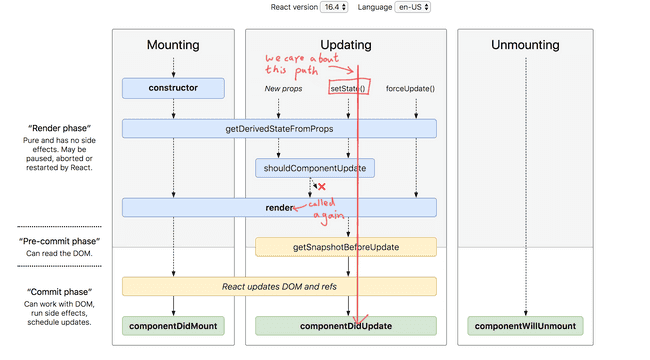

Before we dive into hooks, let's review some lifecycle methods

in the old class syntax.

Here are some important ones that we need to know:

setState: update the state within a component, triggersrendercomponentDidMount: called when a component is just mounted.componentDidMountis allowed to perform side-effect here such as API calls, and state updates withsetStaterender: React callsrenderto get the updated version of the componentcomponentDidUpdate: called after the component re-rendered. Side effects allowed

The lifecycle methods are well summarized in the following flow chart:

See the diagram at: http://projects.wojtekmaj.pl/react-lifecycle-methods-diagram/

Exercise: Build a simple counter component, but the initial value of the counter is given by the server. Here we emulate an API call to fetch the initial value.

// faking a call to the server to get an initial value

function getInitialCounterValue() {

return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(() => resolve(3), 200));

}Click to see solution

class Counter extends React.Component {

state = { count: 0 }

constructor() {

super();

this.onIncrement = this.onIncrement.bind(this);

}

componentDidMount() {

getInitialCounterValue().then(count => {

this.setState({ count });

});

}

onIncrement() {

this.setState(({ count }) => { count: count + 1 });

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h3>{this.state.count}</h3>

<button onClick={this.onIncrement}>Increment</button>

</div>

);

}

}Quick Review of Function Component

For some simple component that has no state (stateless component), using the class syntax can be quite "wordy".

class MyDisplayInfoComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<ul>

<li>Name: {this.props.name}</li>

<li>Major: {this.props.major}</li>

</ul>

);

}

}To get reduce the amount of code we have to write, we can use functions to write component instead of class.

function MyDisplayInfoComponent (props) {

return (

<ul>

<li>Name: {props.name}</li>

<li>Major: {props.major}</li>

</ul>

);

}To simplify it further, we can even use the ES6 arrow function syntax and parameter destructuring assignment.

const MyDisplayInfoComponent = ({ name, major }) => (

<ul>

<li>Name: {props.name}</li>

<li>Major: {props.major}</li>

</ul>

);These stateless components are said to be pure functions. Pure functions are simply functions in programming that obey the property of a mathematical function: given the same input x, it produces the same output y. Stateless components are pure since given the same parameters, they always return the same component, as long as the children components are also stateless.

Overview of Hooks

The function component syntax is nice and simple. Having code that is readable means that it is more maintainable. The function component syntax also makes more sense since you are passing in a bunch of arguments to a function and the function just returns a React Component.

// Here I passed in the argument `name` and `major`

// and this expression should return a React Component.

<MyDisplayInfoComponent name="Galen" major="CS" />However, the problem is that there can be no state within a function component. You cannot even implement a simple counter with just the function component.

With hooks, you can write a counter with a function component.

To keep a state in a function component, we can use the useState hooks.

useState: State in Function Components

The syntax of useState works as such:

// importing the hooks

import React, { useState } from 'react';

// inside the component

const [currentState, setterFunction] = useState(initialState);The useState function takes in an initial state, and returns

an array with 2 elements: the first being the current value of the

state, the second being a function to change the state.

Think of the second function as setState. It is going to trigger

the re-render of the component.

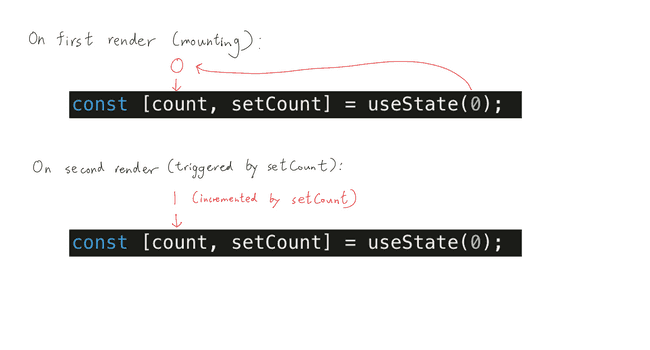

Let's implement a simple counter with useState.

function SimpleCounter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const onClickCallback = () => {

setCount(count + 1);

};

return (

<div>

<p>Count: {count}</p>

<button onClick={onClickCallback}>increment</button>

</div>

);

}Here, the initial state of count will be set to 0.

So the initial count the user see is 0.

Then, we created a callback onClickCallback, for

the button to increment the counter using setCount.

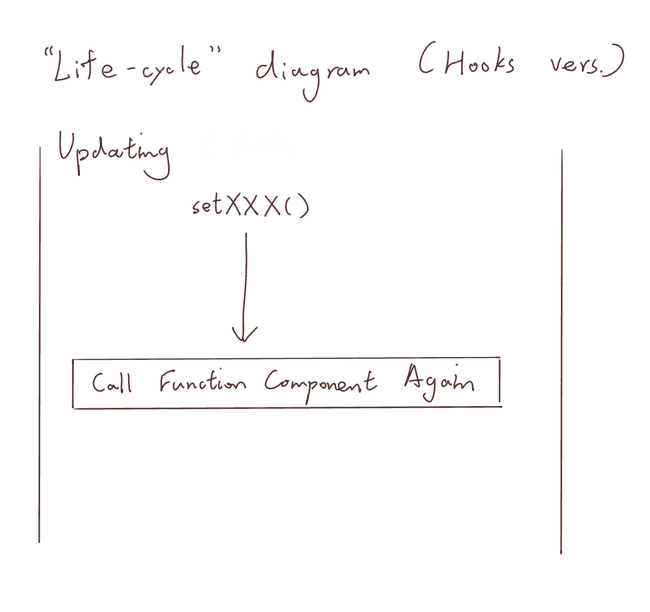

In the a class syntax, a call to setState will causes a

re-render. In other words, the render class method will

be executed again.

How does a functional component, without the render method

re-render then?

Every time you call the setter function returned from

a hook, React is going to re-execute the function component

"function" again.

The reason that you need to re-execute the entire component

function is such that you call the useState hook again to

obtain the current state of the counter.

🍏Application: "Hey React, Set an Alarm" with Multiple useState

Exercise: Can you implement a component that allow an user to select time for an alarm with hooks? An user should be able to increment or decrement the hour and the minute using buttons.

In the previous exercise, you had to keep track of multiple states.

You have two options: 1) you keep an object with useState,

2) you call useState twice.

If we go with option 1, the code would look like this.

function SetAlarm() {

const [time, setTime] = useState({ hour: 16, minute: 0 });

// we ignore the fact that hour/minute cannot be negative

const incrementHour = () => setTime({

hour: hour + 1,

minute

});

const decrementHour = () => setTime({

hour: hour - 1,

minute

});

const incrementMinute = () => setTime({

hour,

minute: minute + 1,

});

const decrementMinute = () => setTime({

hour,

minute: minute - 1,

});

return (

<div>

<h2>Hour: {time.hour}</h2>

<h2>Minute: {time.minute}</h2>

<button onClick={incrementHour}>hour++</button>

<button onClick={decrementHour}>hour--</button>

<button onClick={incrementMinute}>minute++</button>

<button onClick={decrementMinute}>minute--</button>

</div>

);

}If you go with option 2, your code looks like this.

function SetAlarm() {

const [hour, setHour] = useState(16);

const [minute, setMinute] = useState(0);

const incrementHour = () => setHour(hour + 1);

const decrementHour = () => setHour(hour - 1);

const incrementMinute = () => setMinute(minute + 1);

const decrementMinute = () => setMinute(minute - 1);

return (

<div>

<h2>Hour: {hour}</h2>

<h2>Minute: {minute}</h2>

<button onClick={incrementHour}>hour++</button>

<button onClick={decrementHour}>hour--</button>

<button onClick={incrementMinute}>minute++</button>

<button onClick={decrementMinute}>minute--</button>

</div>

);

}Using multiple setState makes our code shorter and more

readable. It also makes more sense since hour and minute

are simply 2 separate counters that has no relationship with

each other. Keeping them in the same object within the same

state is not really necessary.

Notice what we have just said, they are 2 separate counters. This implies they use the same logic. We know one of the important property of functions is to help us abstract and share logic. Can we abstract the counter logic into its own independent functions? Yes!

Introduction to Custom Hooks

Let's implement the counter logic in a function.

function useCounter(initCount) {

const [count, setCount] = useState(initCount);

const increment = () => { setCount(count + 1) };

const decrement = () => { setCount(count - 1) };

return [count, increment, decrement];

}Now, let's use them within our alarm component.

function SetAlarm() {

const [hour, incrementHour, decrementHour] = useCounter(16);

const [minute, incrementMinute, decrementMinute] = useCounter(0);

return (

<div>

<h2>Hour: {hour}</h2>

<h2>Minute: {minute}</h2>

<button onClick={incrementHour}>hour++</button>

<button onClick={decrementHour}>hour--</button>

<button onClick={incrementMinute}>minute++</button>

<button onClick={decrementMinute}>minute--</button>

</div>

);

}We created the useCounter function, which creates a state using useState,

and returns the current state, and 2 setter functions to mutate the state.

useCounter is a custom hook, which is a piece of logic that we composed

using the hooks function (in this case, useState) that React provided.

That is the actual motivation of the new hooks API: sharing logic among

components. Think about using the class syntax, you will have to repeat the logic

for the counter, declare the increment and decrement function twice.

At this point, if you have another component that uses a counter, you

can simply reuse the useCounter custom hook.

This is a really important pattern of logic sharing that React hooks syntax is trying to get at. It changes how we fundamentally write and think about React. If you don't get this now, don't worry. We will re-iterate again with a more involved demo.

useEffect: Side Effect in Function Component

Let's go back to our first exercise. We want to implement a counter with the initial value that depends on a state on the server. How would you go about that in function components with hooks?

function CounterDependingOnServer() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

// spoiler alert: this is WRONG!

getInitialCounterValue().then(val => {

setCount(val);

});

const increment = () => { setCount(count + 1) };

return (

<div>

<h2>Count: {count}</h2>

<button onClick={increment}>count++</button>

</div>

);

}This will trigger an infinite update loop.

When we first render the component, we will call the API

to get the initial counter state. Then, the callback calls

setCount, which triggers a re-render…

We want of think of the entire body of a function component

as the body of render in a class component. If there were

side effects in render, like setState, it can cause

infinite update of our component. Therefore, side effects

are not allowed in the render function, and should

also not be allowed in function component body also.

Note: common side effects include data fetching, setting up a subscription (think media query), and DOM updates.

Think back on how you would do it in a class component.

You will give it a default state first in the constructor first,

and update it later in componentDidMount.

componentDidMount is responsible for executing code

with side effects. Can we use the same approach here?

To execute code after render in a function component,

we use the useEffect hook.

// importing the hooks

import React, { useEffect } from 'react';

// inside the component

useEffect(functionWithSideEffect);When you pass a function to useEffect,

React will execute the function after your component

is rendered every time.

However, we only want to execute it on the first render.

We can keep a state to indicate if we have called the API.

function CounterDependingOnServer() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const [fetched, setFetched] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

if (fetched) return;

getInitialCounterValue().then(val => {

setFetched(true);

setCount(val);

});

});

return (

<div>

<h2>Count: {count}</h2>

<button onClick={increment}>count++</button>

</div>

);

}This works. But this is not the cleanest code.

We have an extra state that is only changed once.

We can actually supply an extra parameter to useEffect

to say tell React we only want this side effect to be

executed once after the first render.

function CounterDependingOnServer() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

getInitialCounterValue().then(val => {

setCount(val);

});

// notice the second parameter we passed in here

}, []);

return (

<div>

<h2>Count: {count}</h2>

<button onClick={increment}>count++</button>

</div>

);

}If you pass in an empty array, you are telling React

to only execute this once, making the useEffect hook

just like componentDidMount.

But why an empty array? What happens if we pass in a non-empty array? This array is called a dependency array, which can help us optimize our application.

🍏Application: "Applying to Boogle" with useEffect

You work for Boogle, a tech company that really cares about good applicant experience during job application. You are writing a React application that let applicants input their information, and back them up every time it is updated.

Let's forget about backing up for a second and build a simple form. First, we will need some state and input fields.

function ApplicationForm() {

const [name, setName] = useState('');

const [email, setEmail] = useState('');

const [school, setSchool] = useState('');

return (

<div>

Name: <input value={name}/>

Email: <input type="email" value={email}/>

School: <input value={school}/>

</div>

);

}Then, we need a onChange handler to capture the value

that user typed in.

function ApplicationForm() {

const [name, setName] = useState('');

const [email, setEmail] = useState('');

const [school, setSchool] = useState('');

const updateName = e => setName(e.target.value);

const updateEmail = e => setEmail(e.target.value);

const updateSchool = e => setSchool(e.target.value);

return (

<div>

Name: <input onChange={updateName} value={name}/>

Email: <input onChange={updateEmail} type="email" value={email}/>

School: <input onChange={updateSchool} value={school}/>

</div>

);

}Let's add a button to submit to application.

But before that, we also want to have a check box to make sure

the applicant agree with our terms and conditions

that they are never gonna read.

function ApplicationForm() {

const [agreeToTerms, setAgreeToTerms] = useState(false);

const [name, setName] = useState('');

const [email, setEmail] = useState('');

const [school, setSchool] = useState('');

const updateName = e => setName(e.target.value);

const updateEmail = e => setEmail(e.target.value);

const updateSchool = e => setSchool(e.target.value);

const updateAgreeToTerms = e =>

setAgreeToTerms(e.target.checked);

const onClickSubmitApp = () => {

// an imaginary application submit function

if (agreeToTerms)

submitApplication(name, email, school);

};

return (

<div>

Name: <input onChange={updateName} value={name}/>

Email: <input onChange={updateEmail} type="email" value={email}/>

School: <input onChange={updateSchool} value={school}/>

<input type="checkbox" onChange={setAgreeToTerms} value={agreeToTerms}/>

By checking this box, you agree to our Terms and Conditions.

<button onClick={onClickSubmitApp}>submit my application</button>

</div>

);

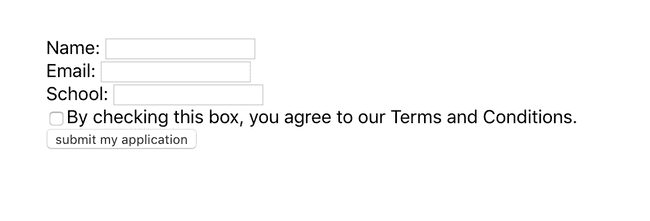

}At this point, you should have something that looks like this (don't worry about CSS and layout):

Now, we want to back up the applicant's input. We want to back it up as frequently as possible. As user update the value of any input fields, we make a backup. We can define an imaginary backup function like this.

// inside the component

const backupOnUpdate = () => {

backup(name, email, school);

console.log('data backed up!');

};We can create a backup upon every keystroke by changing our event listener functions to

const updateName = e => {

setName(e.target.value);

backupOnUpdate();

};

const updateEmail = e => {

setEmail(e.target.value);

backupOnUpdate();

};

const updateSchool = e => {

setSchool(e.target.value);

backupOnUpdate();

};

// we don't need to back up upon agreement

const updateAgreeToTerms = e =>

setAgreeToTerms(e.target.checked);This violates the DRY principle.

We are repeating the back up code 3 times.

Is there an easy way to reduce the amount of code to

type in the class syntax, with the lifecycle

method componentDidUpdate. Since this is called

when state is mutated, we can call backupOnUpdate

in here.

componentDidUpdate() {

const { name, email, school } = this.state;

backup(name, email, school);

}What is the hook-equivalent of componentDidUpdate then?

componentDidUpdate is executed after each render, so is

the useEffect hook!

We can put our update function into useEffect.

function ApplicationForm() {

const [agreeToTerms, setAgreeToTerms] = useState(false);

const [name, setName] = useState('');

const [email, setEmail] = useState('');

const [school, setSchool] = useState('');

const updateName = e => setName(e.target.value);

const updateEmail = e => setEmail(e.target.value);

const updateSchool = e => setSchool(e.target.value);

const updateAgreeToTerms = e =>

setAgreeToTerms(e.target.checked);

const onClickSubmitApp = () => {

if (agreeToTerms)

submitApplication(name, email, school);

};

// componentDidUpdate

useEffect(() => {

backup(name, email, school);

});

return (

<div>

Name: <input onChange={updateName} value={name}/>

Email: <input onChange={updateEmail} type="email" value={email}/>

School: <input onChange={updateSchool} value={school}/>

<input type="checkbox" onChange={setAgreeToTerms} value={agreeToTerms}/>

By checking this box, you agree to our Terms and Conditions.

<button onClick={onClickSubmitApp}>submit my application</button>

</div>

);

}This will back up the data upon every keystroke.

However, do you think this make too many backups?

Consider the user clicking the checkbox to accept the

"Terms and Conditions". It will trigger a render,

since we use a state setter function (setXXX). It will

trigger useEffect but none of the data (name, email,

school) that requires back up has changed.

We want to tell React to only execute useEffect only when

the data that needs to back up has changed. The second parameter

for useEffect is called the dependency array. useEffect

will execute only if any of the value has changed.

useEffect(() => {

backup(name, email, school);

}, [name, email, school]);If any value of the variable name, email and school changes,

the useEffect callback will be executed and performs a backup.

This way, we skipped unnecessary backups that can take up

resources like bandwidth, CPU, memory and such.

Now look back to the pattern of using useEffect as

componentDidMount, we pass in an empty array as the dependency.

That means that "all" the value in the array will never change,

since there are no values. Therefore, the useEffect callback

will only execute on the initial render, acting like

componentDidMount.

Let's validate by writing a mock backup function.

function backup(name, email, school) {

console.log('back up!')

}

For more information, take a look at the official documentation for React: Optimizing Performance by Skipping Effects.

At this point, you can successfully migrate 80% of your class components to function components, using a simple mapping from the old lifecycle method to the new hooks API.

class component |

function component |

|---|---|

this.setState, this.state |

useState |

componentDidMount |

useEffect(cb, []) |

componentDidUpdate |

useEffect(cb, dependencies) |

2 Rules of Hooks

When you are using hooks, you have to follow 2 rules:

- Only call hooks at the top level

- Only call hooks from function components and custom hooks

Read about them here: https://reactjs.org/docs/hooks-rules.html. Focus on the explanation section.

After reading the explanation, can you answer the following questions?

- When

useStateis called, how does React know which state to return? - Can you call hooks from a class component? Why?

- How do you use a hook with a class component (think "out of the box")?

A List Model of Keeping States

When

useStateis called, how does React know which state to return?

The only data passed to useState is the initial state, which

does not contain enough information for React to determine which

state the component wants.

To answer this question, we look at the first rule of hooks.

If hooks are guaranteed to be called at the top level, that means

the hooks will not be inside if-statements or loops or any other

kind of conditional construct.

If such condition is met, the hooks will run in a linear and deterministic manner.

In other words,

- Linear: we know in what order will the hooks be called

- Deterministic: we know how many times will the hooks be called

With nice properties, React can simply keep track of the state for

a component in an array. When useState is called the nth time, React can

return the nth element from the array.

Therefore, the first rule of hooks is very important in the design

of the hooks pattern.

Question 2 and 3 is left as an exercise to the reader. You can find the answer here: https://infinum.co/the-capsized-eight/how-to-use-react-hooks-in-class-components

🍏Application: "Power of Hooks" with Debouncing

"Debouncing" is a rate-limiting technique to reduce the frequency of execution of time-consuming tasks. Some examples include live spell-checking, search suggestion, etc.

Notice the delay in the suggestion popping up after I type some characters into Google. The motivation of debouncing is quite easy to understand: we save useless computation that the user probably won't need. For instance, there is no point to return a list of suggestion for the search keyword "reac" when the user will finish typing in less than 100ms and actually search for the keyword "react".

Let's see how we can implement a search bar with debouncing. First, a mock function to emulate a suggestion algorithm.

async function getSearchSuggestions(input) {

const results = [

'How to ' + input,

input + ' with my grandma',

'What is ' + input,

'Who is ' + input,

input + ' in Los Angeles',

'free ' + input,

];

// shuffle the result a bit

results.sort(() => Math.random() - 0.5);

return results;

}Here is an outline of how debouncing works:

when "value" is updated (from typing):

if an "action" is scheduled previously

cancel the "action"

schedule an "action" to execute after a given delayIn other words, debouncing will execute the "action" if the "value" has not updated for some amount of delay.

setTimeout and clearTimeout

We already know how to trigger a side-effect when a

value is updated with useEffect. But how do we delay

the side effect?

In JavaScript, we can schedule callback to execute after

a delay using setTimeout, which returns a timer handle

that can be used to cancel the task with clearTimeout.

setTimeout(() => console.log('timeout in 500ms'), 500);

const timerID = setTimeout(() => console.log('will be cancelled'), 500);

clearTimeout(timerID);

const timerID2 = setTimeout(() => {

console.log('will be cancelled before firing')

}, 600);

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('cancelling timerID2 100ms before it is executed');

clearTimeout(timerID2);

}, 500);

// output:

// timeout in 500ms

// cancelling timerID2 100ms before it is executedKnowing the setTimeout mechanism, we can now implement a search

bar that is debounced!

Implementation

We start with a simple search bar without debouncing.

function SearchBar() {

const [search, setSearch] = useState('');

const updateSearch = e => setSearch(e.target.value);

return (

<div>

<input onChange={updateSearch} value={search} />

</div>

);

}Let's implement our debouncing logic. We know that we want

to execute it when the value of search has changed. Using

useEffect, we can execute getSearchSuggestions when

search is udpated.

const [suggestions, setSuggestions] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

// get search suggestions…

if (search === '') {

setSuggestions([]);

return;

}

getSearchSuggestions(search).then(results => {

setSuggestions(results);

});

// when search is updated

}, [search]);

// display the suggestions

return (

// …

<ul>

{suggestions.map(s => <li>{s}</li>)}

</ul>

)Now, we delay the operation by a given amount of delay.

function SearchBar() {

const [search, setSearch] = useState('');

const updateSearch = e => setSearch(e.target.value);

const [suggestions, setSuggestions] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

// delay getting search suggestions

setTimeout(() => {

if (search === '') {

setSuggestions([]);

return;

}

getSearchSuggestions(search).then(results => {

setSuggestions(results);

});

}, 500); // by 500ms

}, [search]);

return (

<div>

<input onChange={updateSearch} value={search} />

<ul>

{suggestions.map(s => <li>{s}</li>)}

</ul>

</div>

);

}However, this will only delay all get search suggestions

operations by 250ms, because we never cancel the previous

operation.

To implement our debouncing logic, we need to keep a

timer state, so we can cancel it later with clearTimeout.

function SearchBar() {

const [search, setSearch] = useState('');

const updateSearch = e => setSearch(e.target.value);

const [suggestions, setSuggestions] = useState([]);

const [timer, setTimer] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

// cancel previous operation

clearTimeout(timer);

const id = setTimeout(() => {

if (search === '') {

setSuggestions([]);

return;

}

getSearchSuggestions(search).then(results => {

setSuggestions(results);

});

}, 500);

setTimer(id);

}, [search]);

return (

<div>

<input onChange={updateSearch} value={search} />

<ul>

{suggestions.map(s => <li>{s}</li>)}

</ul>

</div>

);

}There you go. You have a working debounced search bar.

Cleaning up useEffect

However, the logic is convoluted since we now keep track of

an extra state of timer just for the cancelling the

previous scheduled operation.

We are cleaning up after side effects of the previous

useEffect.

In fact, this pattern is common enough that the React

team decides to make an API for it.

In the callback of useEffect, you can return a function

that will help you clean up.

useEffect(() => {

const id = setTimeout(() => {

if (search === '') {

setSuggestions([]);

return;

}

getSearchSuggestions(search).then(results => {

setSuggestions(results);

});

}, 500);

return () => {

clearTimeout(id);

};

}, [search]);The clean up function will be called before the next

useEffect callback is triggered.

Now the code is simpler since we can get rid of the

timer state variable.

function SearchBar() {

const [search, setSearch] = useState('');

const updateSearch = e => setSearch(e.target.value);

const [suggestions, setSuggestions] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

const id = setTimeout(() => {

if (search === '') {

setSuggestions([]);

return;

}

getSearchSuggestions(search).then(results => {

setSuggestions(results);

});

}, 500);

return () => { clearTimeout(id); }

}, [search]);

return (

<div>

<input onChange={updateSearch} value={search} />

<ul>

{suggestions.map(s => <li>{s}</li>)}

</ul>

</div>

);

}Here is a question for you:

Can we use an async function as the first parameter to

useEffect?

Abstract, Reuse, Custom Hook

Debouncing is a fairly complex piece of logic. However, with the power of react hooks, we can abstract and reuse this piece of logic very easily.

function useDebounce(value, action, delay) {

useEffect(() => {

const id = setTimeout(() => action, delay);

return () => { clearTimeout(id); }

}, [value, action, delay]);

}

function SearchBar() {

const [search, setSearch] = useState('');

const updateSearch = e => setSearch(e.target.value);

const [suggestions, setSuggestions] = useState([]);

const updateSuggestion = () => {

getSearchSuggestions(search).then(results => {

setSuggestions(results);

});

};

// this one line implements a debounce logic!!!!

useDebounce(search, updateSuggestion, 250);

return (

<div>

<input onChange={updateSearch} value={search} />

<ul>

{suggestions.map(s => <li>{s}</li>)}

</ul>

</div>

);

}Another way of implementing the useDebounce hook

is to return the debounced value.

function useDebounce(value, delay) {

const [debounced, setDebounced] = useState(value);

useEffect(() => {

const id = setTimeout(() => {

setDebounced(value);

}, delay);

return () => { clearTimeout(id); }

}, [value, delay]);

return debounced;

}In this implementation, we debounce the value of the

debounced state variable, and return that to the caller

of this hook. Here is a question for you.

How do we debounce callback with this implementation of

useDebounce?

We can use useEffect. useEffect is called when

its dependency variable changes. Since the update

to the debounced variable is debounced, we can

let a useEffect callback depends on that variable.

function SearchBar() {

const [search, setSearch] = useState('');

const updateSearch = e => setSearch(e.target.value);

const [suggestions, setSuggestions] = useState([]);

const debouncedSearch = useDebounce(search, 250);

useEffect(() => {

getSearchSuggestions(debouncedSearch).then(results => {

setSuggestions(results);

});

}, [debouncedSearch]);

return (

<div>

<input onChange={updateSearch} value={search} />

<ul>

{suggestions.map(s => <li>{s}</li>)}

</ul>

</div>

);

}To show you why this is easy to reuse, I am going to build a spell checker.

function SpellChecker() {

const [word, setWord] = useState('');

const updateWord = e => setWord(e.target.value);

const [isCorrect, setIsCorrect] = useState(true);

const debouncedWord = useDebounce(word, 250);

useEffect(() => {

spellCheck(debouncedWord).then(correct => {

setIsCorrect(correct);

});

}, [debouncedWord]);

return (

<div>

<input onChange={updateWord} value={word} />

<h2>

{isCorrect ? 'Correct' : 'Wrong'}

</h2>

</div>

)

}For building any component with debouncing, we can

just use the useDebounce.

With hooks, we can share the debounce logic among

different components. In fact, you can make your

code into a package and publish it online for other

people to use it!

(Check out rehooks.com. It is a collection of hooks

that has been published as NPM packages.)

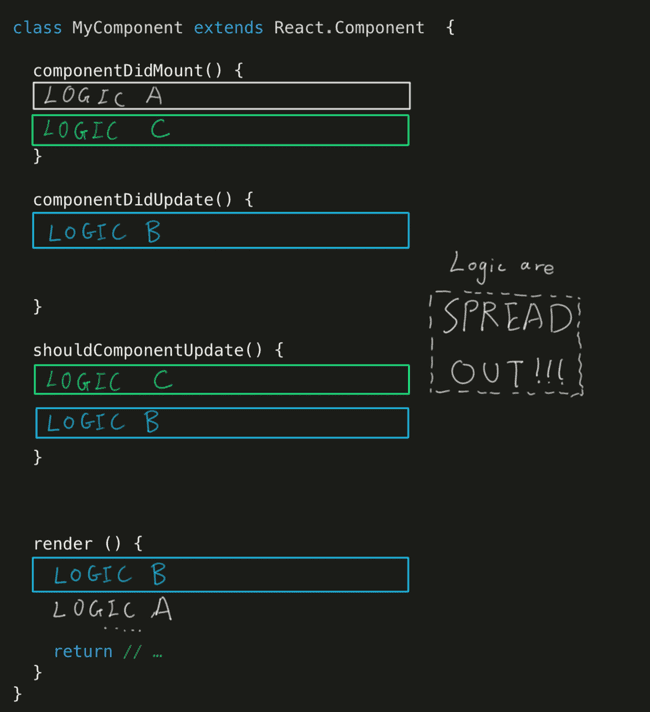

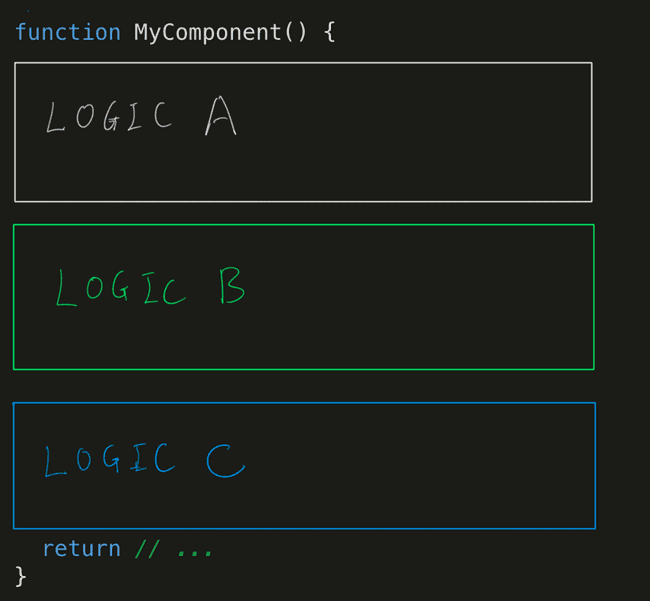

What's Wrong with the Old class Way?

In a class component, logic can be distributed across

multiple lifecycle methods.

It is hard to abstraction the logic out to a reusable standalone component/function.

However, the logic is compact with hooks.

If the code that belongs to the same object is close together, it is easy to abstract them into their own custom hooks or functions. The new pattern enables you to play with logic as LEGO blocks and insert them into any place you want.

You can read about the motivation behind the new hooks API from the React team: https://reactjs.org/docs/hooks-intro.html#motivation

Final Challenge

I am going to build a counter that increments itself every X second.

function SelfIncrementingCounter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

setInterval(() => {

setCount(count + 1);

}, 200);

});

return <h1>Count: {count}</h1>;

}Note:

setIntervalschedule a callback to execute for some interval. In this case,setCountis called every 200 ms.

But this implementation does not work. Can you explain what is the wrong behavior?

Click to see answer

useEffect is called on every render, since there is no

dependency array specified.

Each time useEffect is executed, it start a repeated scheduled task.

The number of repeated scheduled tasks grows exponentially.

There are races between the different tasks leading to a glitch.

The previous attempt failed. I try again, passing an empty

dependency array such that the useEffect callback is only

executed once after the first render (like componentDidMount).

function SelfIncrementingCounter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

setInterval(() => {

setCount(count + 1);

}, 200);

}, []); // added empty dependency array here

return <h1>Count: {count}</h1>;

}Does this work? (Hint: it does not) Why?

This one might be a bit hard. Here is some hint:

- There can be multiple copies of

count. Why? - There can be multiple versions of the callback function

passed to

useEffect, which one doesuseEffectuse? - In the executed version of callback function, which

copy of

countis thecountreferring to?

Now we know that it works, can we implement a version

that works? Hint: the setter setXXX function for state

can also takes a function as a parameter.