Multi-threading in JavaScript: Worker Threads

JavaScript Chats with ACM Hack Session 5

November 11, 2019

- An overview of multi-threading

- Different kinds of multi-threading

- Creating a Web worker

- Inter-thread communication

- When should we use multi-threading?

- Libraries for multi-threading

An overview of multi-threading

For the past decade, computer-makers have realized that there are physical limits to the performance of a CPU. At some point, newer CPUs can no longer process each instruction much faster than the previous generation of CPUs – and it is clear that we are nearing that point. The key to increasing computer performance then rests in the ability to process multiple instructions simultaneously by packing more “cores” onto each individual CPU, rather than making each core faster.

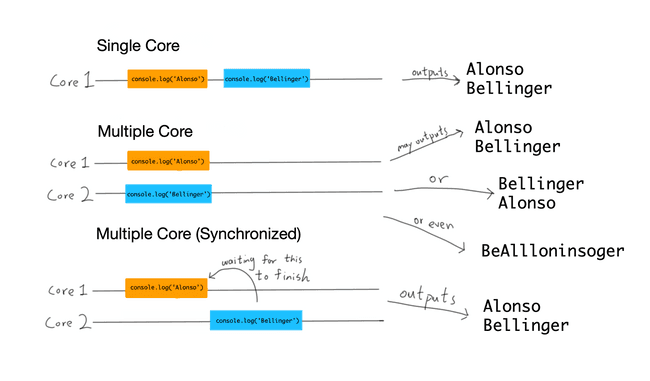

Unfortunately, programs designed to run on a single thread (or CPU core) are unable to automatically take advantage of the increasing number of cores on a system. One of the reasons for this is the problem of synchronization. Single-thread programs assume a linear order of execution; to wit, with the following piece of JavaScript code, we expect “Alonso” to be printed before “Bellinger.”

console.log('Alonso');

console.log('Bellinger');Now consider the case where this program runs in a multi-threaded fashion, with each of these statements running on a different core. There then would be no guarantee to the order of output: the first statement could finish later than the second, or it could start later but finish sooner, or it could even run just as expected, starting and finishing before the second statement runs. To recover the single-threaded behavior, we’d have to make the two CPU cores synchronize with each other before and after statement – which essentially defeats the purpose of using multiple cores.

Even though multi-threading doesn’t work too well with this application, as we will soon see, there are many JavaScript programs where multi-threading is able to provide a huge boost in performance. It does however take a human – not a machine – to identify if and how multi-threading could improve the performance.

Different kinds of multi-threading

Different programming languages support multi-threading differently.

Many traditional languages like C, C++, and Java all support shared-memory multi-threading. In this régime, two threads belonging to the same program have access to the same variables. A thread can modify variables and other in-memory objects that belong to another thread.

On the other hand, JavaScript (until very recently) does not support shared-memory multi-threading at all. In JavaScript traditionally, for two threads to communicate with each other, they have to explicitly send “messages” to the other thread. Any objects that are sent through the communication channel are copied, so there is no way for two JavaScript threads to read the memory of the other thread.

Question: What are some pros and cons for each approach of multi-threading? Why do you think JavaScript doesn’t use shared-memory multi-threading?

Here is an answer.

Shared-memory multi-threading is easy to get started with. You pretty much do the same things as regular single-threaded programs. There is very little overhead when using single-threaded programs: no need to clone objects like one does in JavaScript, etc.

However, shared-memory multi-threading requires explicit synchronization (spinlocks and mutexes) in order to avoid race conditions. Even with locking, it’s easy to introduce bugs into a program.

From the very beginning, JavaScript is designed to be robust. There are no undefined behaviors in the language, unlike C and C++. Shared-memory multi-threading introduces the possibility to do Very Bad Things™ to the program, and so browsers decided not to take that path when introducing the feature.

Creating a Web worker

Enough talk. Let’s spawn a thread in JavaScript.

We will use the Web Workers API that exists in web

browsers, though Node.js provides a very similar API through its

worker_threads module.

<!-- index.html -->

<!doctype html>

<body>

<script>

console.log('Before spawning a worker');

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

console.log('After spawning a worker');

</script>

</body>// worker.js

console.log('We are in a worker!');Visiting index.html would result in the following being printed in the

DevTools console:

Before spawning a worker

After spawning a worker

We are in a worker!When we get into the DevTools in the Sources tab, we see that there is now a

“Threads” section there is now a worker.

From now on, we will call the index.html thread the main thread, and

the worker… the worker thread.

Recall from session 2 that every JavaScript environment in

the browser has an event loop.

If a task runs for too long, it could make the whole page unresponsive.

Indeed, if we were to put an infinite loop in the <script> element in the

HTML file, we do indeed see that the page stopped responding.

The task on the main thread has blocked the event loop.

<body>

+ <button>Test</button>

<script>

console.log('Before spawning a worker');

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

console.log('After spawning a worker');

+

+ while (true) continue;

</script>

</body>However, if we put the loop in worker.js instead, the page would still

responsive.

This tells us that each worker thread gets its own event loop.

Inter-thread communication

As mentioned earlier, to communicate between threads, the Web Workers API generally requires the use of message-passing. Here’s an example.

// part of index.html

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

// When a message is received from the worker thread…

worker.onmessage = msg => {

console.log('Received message from the worker:', msg.data);

};// worker.js

setInterval(() => {

// Send a message to the main thread.

postMessage('hello world!');

}, 500);We observe that every 500 ms (or every half-second), the text “Received message from the worker: hello world!” gets printed to the JavaScript console. Here, we are sending messages from the worker thread to the main thread.

We can send objects too, not just strings:

// worker.js

setInterval(() => {

postMessage({

timestamp: Date.now(),

status: 'Healthy'

});

}, 500);And now we see that the object gets printed to the console through the

worker.onmessage function.

Similarly, we can pass messages from the main thread to the worker thread, by

calling worker.postMessage() from the main thread and setting the

self.onmessage event handler in the worker.

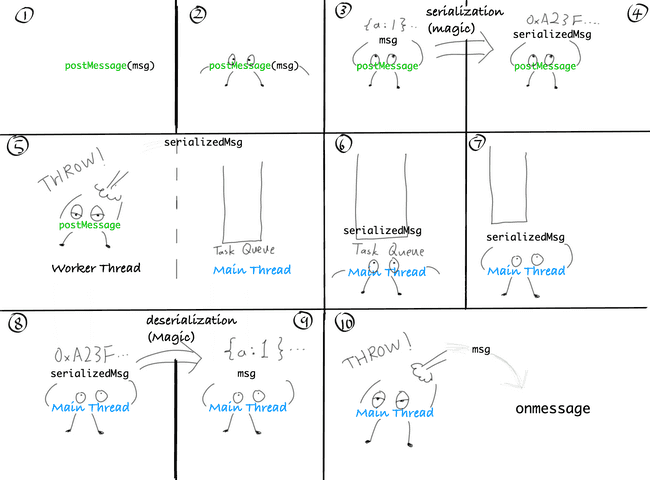

Structured serialization/deserialization

Let’s now try something a bit trickier. Let’s modify the object sent from the worker thread, in the main thread.

// part of index.html

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

worker.onmessage = msg => {

const obj = msg.data;

obj.count += 1;

};// worker.js

const obj = { count: 0 };

setInterval(() => {

console.log(obj.count);

postMessage(obj);

}, 500);We expect the output to be an ascending sequence of integers with a new line printed every half-second, starting with 0. However, what we actually observe is that a 0 is printed every half-second.

Question: Why is this the case? (Hint: this has to do with the fact that JavaScript does not use shared-memory multi-threading.)

Recall that earlier we mentioned that JavaScript in general does not allow shared-memory multi-threading. Whenever an object is sent from the worker to the main thread (or vice versa) as a message, the object is cloned (copied).

In the HTML Standard and also in a variety of other sources, the cloning algorithm has a special name: “structured serialization/deserialization,” or “structured cloning.” Unlike some other methods of cloning objects in JavaScript, structured serialization/deserialization has some special properties that make them extra “good”:

- Deep cloning: not just the message object itself is cloned, but also

all of its properties.

Object.assign()and the object spread syntax{ ...obj }only create shallow clones. - Deals with cycles: the commonly-used deep-cloning idiom of

JSON.parse(JSON.stringify())does not work if there is a cycle in the property graph (e.g., ifobj.a === obj). Structured cloning works just fine with that. - Preserves (most) built-in objects:

JSON.parse(JSON.stringify())does not preserve built-in objects likeDateobjects. Structured cloning works just fine.

There still remain certain data types that cannot be cloned, like functions

and Error objects. But that doesn’t seem too bad.

(Advanced) Structured “cloning” with… transfer?

Having to copy things all the time seem quite wasteful. We must be able to think of something better that still avoids the synchronization problem, right?

With certain objects like ArrayBuffer objects (that just represent

sequences of bytes), instead of copying it we could transfer the bytes from

one thread to another.

Let’s see it.

// main thread

const arr = new Uint8Array([0, 1, 2]);

worker.postMessage(arr, [arr.buffer]);

console.log('After transfer:', arr);// worker thread

self.onmessage = msg => {

console.log('In worker:', msg);

};Here, no copying of the Uint8Array object is done (fast!).

But we see that after the transfer arr becomes empty.

This maintains the invariant (guarantee) that no two distinct JavaScript

threads may access the same object at the same time.

Conclusion

Altogether, the process of sending a message could be summarized by the following comic:

When should we use multi-threading?

This is, of course, the million-dollar question.

Question: Any ideas? What do we look for in an application for which multi-threading may be beneficial?

There are answers to this question that are programming language-agnostic, but let’s focus on the JavaScript-specific reasons.

Here are a few rules of thumb:

- Heavy computation that could take a while to finish should be moved to worker threads. We never want to block the main thread, as it’s tied to the UI responsiveness.

- Work that is relatively independent of the UI could be in workers. We can only operate the UI from the main thread, and the communication overhead could be quite palpable if many DOM operations are being done.

An example where Web Workers are used in concert with DOM APIs is PDF.js, a PDF viewer written by Mozilla in JavaScript and the default PDF viewer in Firefox. The hard-core file parsing and number crunching routines are all done on a worker thread. The results are then posted to the main thread, where they are rendered into DOM elements.

Libraries for multi-threading

To help with the awkwardness of the postMessage() APIs, Google has created

a library called Comlink that makes communicating with a worker as

easy as calling an asynchronous function.

Google has also experimented with other worker-based technologies, like worker-dom, which provides a DOM for web workers to manipulate and then batches the DOM mutations to be sent to the main thread at once.